Beyond the presence of former Gov. Nikki Haley and the BMW plant in Spartanburg, South Carolina has always been an unusual state. Yet its racial caste system – and how it keeps Black children from gaining high-quality education – makes it as normal as Wisconsin and Mississippi.

After Europeans arrived, they settled it with enslaved people from the rice growing regions of West Africa, who used their traditional knowledge and skills to turn the Low Country into a major source of food and indigo for the first British Empire. The slave owners, who seldom visited the malarial plantations along the coast, grew rich. The slaves, who survived, remained slaves. Away from the coast, the Piedmont foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains were settled by Scotch-Irish migrants working their way down the Appalachian Mountains.

This immigration pattern can still be seen today in the demographics of the state. The western-most counties are nearly entirely White. Though the coastal counties are now populated by White immigrants from outside the state, the Low Country is still mostly-Black.

At the beginning of the twentieth century most farms in the center of the state were worked by tenants and sharecroppers, many of whom were White, but most of whom were Black, and they were still the majority of the state’s population. The textile and tobacco factories that were becoming common were the scenes of union organizing alternating with violent strikebreaking against the impoverished workers, Black and White, men and women.

Fitting for the place where Denmark Vesey and others were executed for leading a slave revolt at the beginning of the 19th century, Jim Crow was particularly severe in South Carolina. The Black population disenfranchised, allowed only minimal education. J. E. Swearingen, then the state’s Superintendent of Education, wrote in his 1915 Annual Report: “The Negro . . . cannot remain ignorant without injury to himself, his white neighbors, and to the commonwealth. [On the other hand, h]is training should fit him to do the work that is open to him.” That year, according to researcher Elspeth Smith-Stuckey, more than 90 percent of the segregated schools for Black children had only one teacher. In 1920, Superintendent Swearingen’s “reform” budget asked for $5 per Black student and $$25 per White student.

The Great Migration saw much of the Black population of the state move north, leaving more than one million descendants of enslaved Africans now living in the state continuing to suffer from the heritages of slavery and Jim Crow. Today, Black South Carolina residents are concentrated, not in the Low Country, but in a band across the middle of the state from Allendale to Marion counties, where they form more than half the population. These counties are among those in the state with the lowest per capita income and the lowest percentage of college graduates.

There is little inter-generational income mobility in South Carolina. Nowhere in the state are a child’s chances of reaching the top fifth of the national income distribution, given parents with incomes in the bottom fifth, greater than 5 percent. That is the average for all state residents.

It is much worse for South Carolina’s African-American residents. The Opportunity Atlas produced by Raj Chetty’s group, now at Harvard, tells us that Black children born in low-income families in Charleston County, on the South Carolina coast, as adults, on average have incomes of $24,000 (less than half the national figure), an incarceration rate of 5.6 percent, a high school graduation rate of 73 percent and a college graduation rate of 17 percent. The average Black student in the Charleston schools attends a school where two-thirds of the students are from poor families, while the average White student attends a school where just 42 percent. of the students are poor.

White adults, who as children were born into low-income families in Charleston County, on average have incomes of $35,000, an incarceration rate of 1.8 percent, a high school graduation rate of 81 percent and a college graduation rate of 24 percent. In other words, there is a $11,000 penalty for being born Black in Charleston County.

In this comparatively wealthy part of South Carolina, the chances for inter-generational upward mobility are practically inexistent for Black children.

In majority-Black Allendale County, three counties up-state from Charleston, Black children born in low-income families, as adults, on average have incomes even less than those in Charleston, $21,000, incarceration rates of 2.5 percent, a high school graduation rate of 70 percent and a college graduation rate of 19 percent, while their White peers, with the same high school graduation rate and a lower college graduation rate (15 percent), have household incomes of $32,000 and an incarceration rate of less than 1 percent.

The penalty for being born Black in Allendale County, as in Charleston County, is $11,000 less in income and twice the chance of incarceration.

The chances are similar for inter-generational mobility for those born into high-income households. In Allendale County, a White child born into a high-income family can look forward to a household income of $54,000—$12,000 more than a White child born into a low-income family in the county. A Black child born into a high-income family in Allendale County can look forward to achieving a household income of $29,000—$8,000 more than a Black child born into a low-income family in the county, but $3,000 less than a White child born into a low-income family in the county.

In Charleston County, a White child born into a high-income family can look forward to a household income of $52,000—$17,000 more than a White child born into a low-income family in the county. A Black child born into a high-income family in Charleston County can achieve, on average, a household income of $36,000—$15,000 more than a Black child born into a low-income family in the county, but only $1,000 more than a White child born into a low-income family.

In spite of the comparatively low rates of White college graduation in Allendale and similar counties, state-wide, the percentage of White college graduates is more than double that of Black college graduates. More of the state’s Black residents have not finished high school (18 percent) than have graduated from college (15 percent). This has a direct effect on family and household income, as college graduates are paid more than twice what workers of the same race with less than a high school diploma are paid and those with a doctoral degree are paid three times as much as those of the same race with less than a high school diploma.

Black households South Carolina are poorer than White residents of the state and poorer than the national average for Black households. This is to be expected. It’s the legacy of White people brutally enslaving and oppressing enslaved Africans, especially after the execution of Denmark Vesey, the founder of Mother Emanuel A.M.E. Church, and others for allegedly plotting a slave revolt.

Sixteen percent of Black families in South Carolina somehow live on incomes of less than $10,000 a year, nearly three times the percentage of similarly deprived White households. The national median White household income is $63,700, for Black households it is $40,200. In South Carolina it is $58,500 for White households and only $32,200 for Black households. The median Black family income is just over half that of White, non-Hispanic, families. In South Carolina, more than four times the percentage of White households as Black households have incomes over $200,000 per year: 4 percent compared to less than 1 percent. More than twice the national average percentage for all Americans, 42 percent, of South Carolina’s African-American households are in the bottom fifth of the national income distribution and only 7 percent have incomes in the top 20 percent of the national income distribution.

Nearly forty percent of school-age Black children in South Carolina live in poverty. Unless there is a change in the state’s education system, things will stay that way.

The National Institute for Early Education Research ranks South Carolina as 11th among the states for access to pre-school enrolling 41 percent of its 4-year-olds in state supported pre-kindergarten programs. But it ranks only 38th for resources provided to pre-kindergartens. High quality early childhood education programs have been shown to have positive effects on primary school learning. However, in South Carolina, with its deficient funding of prekindergarten, and below average K-12 per student expenditures, by fourth grade nearly two-thirds of African-American students in the state’s public schools are assessed by the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) as functionally illiterate (“below basic”) and just 15 percent have the expected reading skills for that grade. The comparable percentages for the state’s White students are reversed: 40 percent reading proficiently and less than a third with skills that are judged as below basic.

The educational opportunities in the primary grades in South Carolina are clearly differentiated by race. As reported by NAEP, the state’s White fourth-graders, whether from lower- or middle-income families, read at the national averages for each of those groups. Black fourth-graders from lower-income families, that is, most Black families, have lower achievement levels than the national average for lower-income Black children. The state’s Black-White gap for lower-income student is 19 percentage points in favor of White students among those students reading at grade level. Although fourth-graders from the state’s relatively small number of middle-income Black families have higher achievement levels than the national average for their group. Among middle-income students the gap is a virtually identical 20 percentage points in favor of White students at the proficient level.

Black students in South Carolina are twice as likely as White students to be functionally illiterate in fourth grade and are only a third as likely to be taught to read proficiently.

By eighth grade, the percentage (48 percent) of South Carolina’s Black students who are functionally illiterate has declined slightly from the percentage at fourth grade, but so has the percentage (11 percent) reading at grade level. The White-Black gap is 30 percentage points among proficient readers and the Black-White gap is also 30 percentage points among those assessed as reading below basic, both gaps having widened after four years of schooling. More than half of the state’s Black students from lower-income families are functionally illiterate at grade eight, as are nearly a third of Black students from middle-income families.

While 22 percent of Black students from middle-income families read at grade level, only a negligible 8 percent of those Black students from lower-income families have been taught by the South Carolina schools to be proficient readers. A White, non-Hispanic, student from a lower-income family is more likely to read proficiently than a Black student from a middle-income family and less likely to have been left functionally illiterate by their school. Having college-educated parents gives White students in South Carolina a 33 percentage point advantage over those with parents without a high school diploma, but the gap between Black students with college-educated parents and those with only a high school education is just 7 percentage points. A White student whose parents did not finish high school is more likely to be taught by their school to read proficiently than a Black child of college graduates.

Negative school effects in South Carolina overwhelm family education levels for Black children.

South Carolina fails to educate both Black and White children to the national averages for those groups, White children only marginally less, Black children very much less well. While nationally, in 2017, 18 percent of Black children in grade 8 read “proficiently” or above according to NAEP, in South Carolina just 11 percent achieved that level. There has been some progress in the reading levels of Black children nationally; there has been none for Black children in South Carolina.

One explanation for these differences in educational opportunities might be found in the historic and continuing racial segregation of the schools in South Carolina. According to data from Brown University’s US Schools index, in the Charleston metropolitan area, for example, where half the students are White and over one-third are Black, a White elementary school student is likely to be in a school where two-thirds of the other students are White, while a Black elementary student will be in a school that where over half the other students are Black. Due to persistent segregation the average Black student will be in a school that is 62 percent poor, regardless of the income level of that student’s own family.

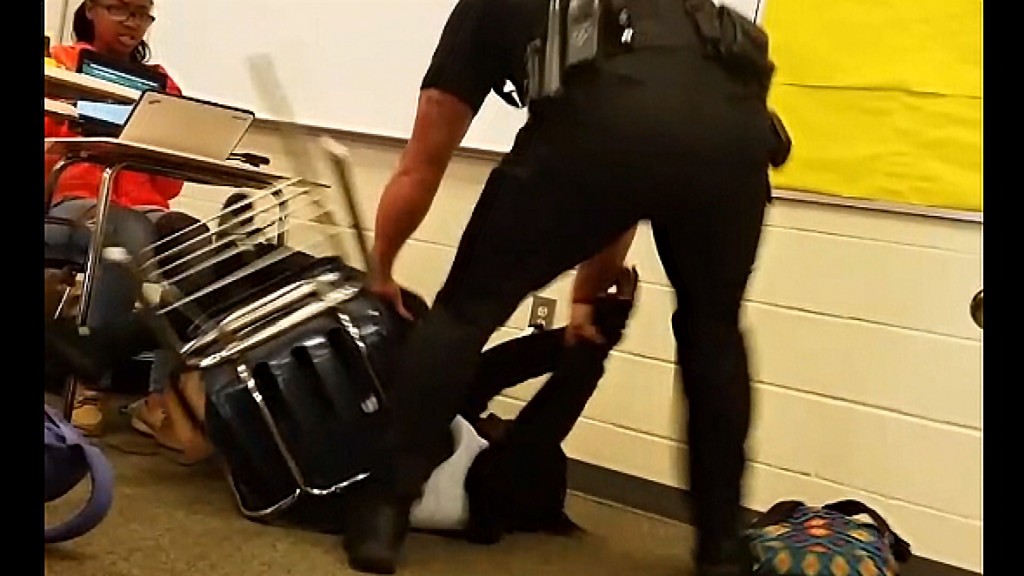

Another factor restricting educational opportunities is school discipline practices. The latest year for which state-level school discipline data is available from the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights is 2013-14. That year, 35 percent of students in South Carolina were Black and 53 percent White, but 61 percent of students given at least one out-of-school suspension were Black as compared to 31 percent who were White. Research has shown that school discipline rates are in large part determined by racial attitudes of teachers and administrators. Higher rates of out-of-school suspensions and expulsions are associated with repeated grades and failure to graduate from high school.

The educational opportunities available in South Carolina’s schools culminate with (or without) high school graduation. According to the South Carolina state “report card,” the 4-year adjusted cohort graduation rate reported by South Carolina for the 2016-17 school year was 83 percent for Black students and 86 percent for White students. However, the percentage of students meeting the ACT College-Ready Benchmark in English was only 17 percent for Black students (and 53 percent for White students). Just half of African-American students in South Carolina who took the SAT in 2018 met the College Board’s College and Career Readiness Benchmark in English, compared to 86 percent of White students. Half of Black SAT test takers met neither the English nor the Math Benchmark, as compared to just 12 percent of White South Carolina test-takers. If a South Carolina high school diploma were meaningful, this would give a graduation rate of just over 40 percent, rather than 83 percent, for Black students.

South Carolina no longer has legally segregated schools, but its schools remain largely segregated by race and doubly so by income. The result is that although nearly a quarter of Black students from middle-income families in the state are taught to read at the expected level in middle school, fewer than a tenth of Black students from lower-income families are taught to read proficiently and half are left functionally illiterate. Even those Black students from middle-income families are only half as likely to be taught to read proficiently as are their White peers and nearly a third of them are left functionally illiterate. The consequences can be seen in the Bureau of the Census’s economic and educational attainment data for the state given above. South Carolina’s Black citizens remain in the situation defined for them by the Founder’s at three-fifths of that of their White neighbors.